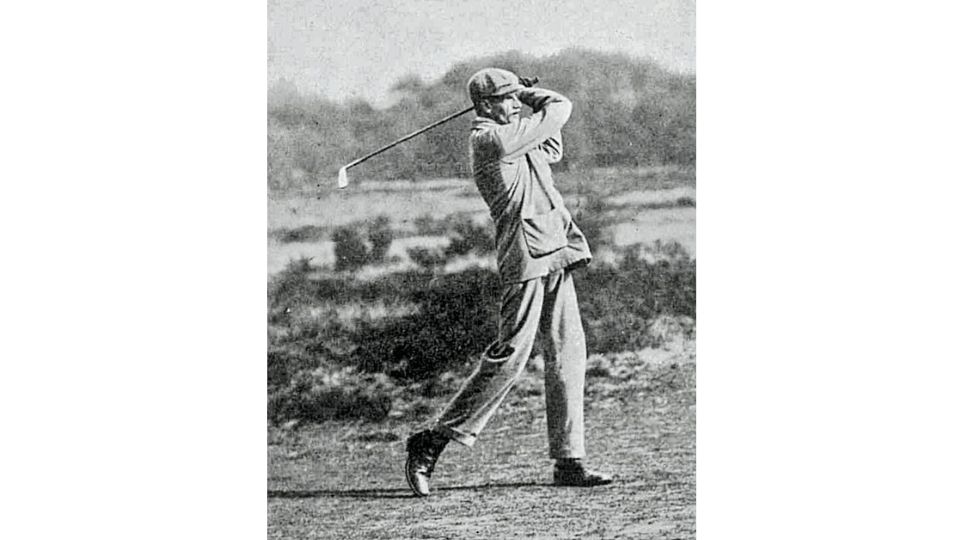

Golf Architect Hugh Alison was in 1883 to a well off family in Preston, England. An accomplished sportsman, he played both golf and cricket at Oxford. He was a better athlete than a student, never graduating from the prestigious university.

From Unsuccessful Student to Architect

Becoming the Secretary of Stoke Poges GC (now Stoke Park) he would assist H.S.Colt in its construction. Shortly after that, he would help Colt with St. George's Hill and Camberley Heath. His internship was interrupted by the Great War. Alison would pick up where he left off in 1919, joining forces with HS Colt and Alister MacKenzie to form Colt, MacKenzie and Alison. The firm would remain intact until 1923 when MacKenzie would leave, and John Morrison would take his place. Colt took most of the work in Britain while Hugh travelled extensively in the USA and the Far East. A highlight of his time stateside is the esteemed course at Pine Valley.

Lasting Legacy

Despite a portfolio of more than 20 courses stateside it is his design work in Japan for which Hugh Alison is best known. Fugi, Tokyo, Hirono and Kawana would set the benchmark for golf in Japan for decades to come.

A Closer Look

We wish to thank friend of Evalu18 and collaborator, Keith Cutten, for the material for this short biography. For a more detailed account, you can find his book, The Evolution of Golf Course Design.

Hugh Alison also contributed to HS Colt's book, Some Essay's on Golf Course Architecture. Also, the book Golf Courses: Design, Construction and Upkeep includes a contribution from Alison.